|

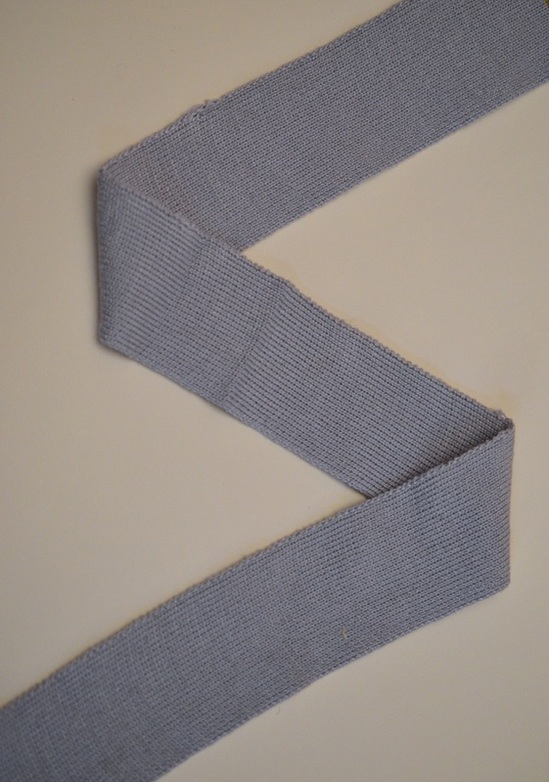

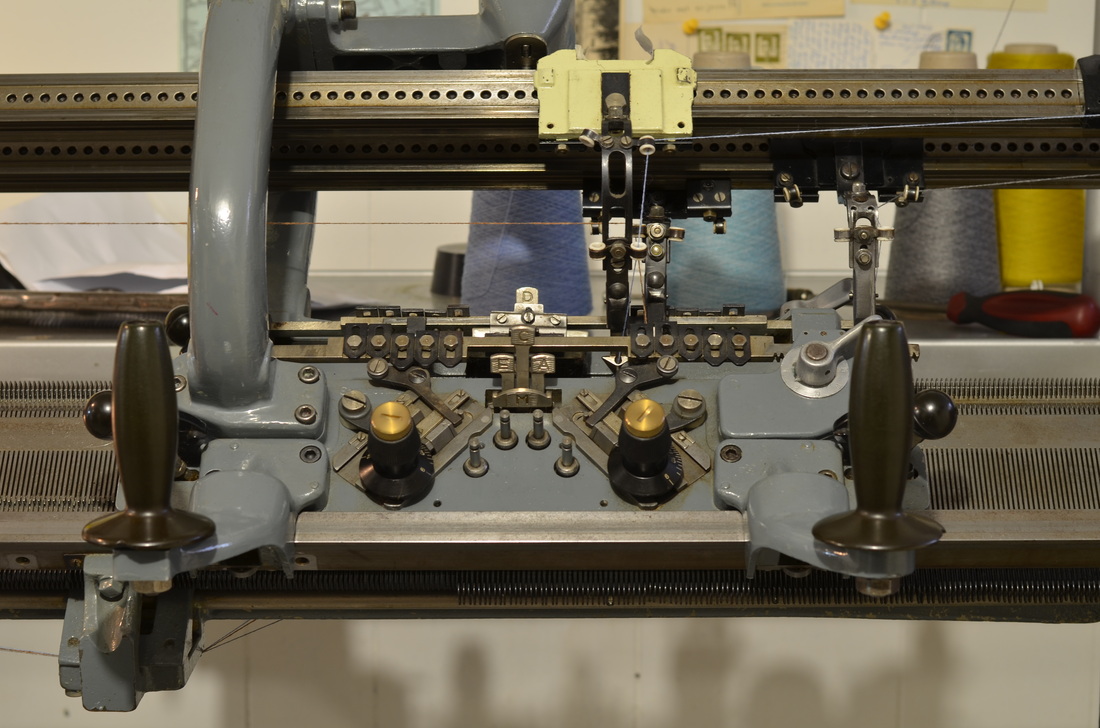

In my previous post I talked about how production is "not a random" act. The physical representation of an idea is subject to technical and knowledge frameworks as well as the mode of production. Well, here are some examples of production limitations! I am trying to make my own version of Edwardian lace banding and fagotting through knitting. As you can see there are areas of success and areas where the machine was unhappy. I think this is a great example of the way production funnels your ideas based on the process. These bands are essentially 1X1 rib in very fine yarn guages. The fagotting effect was created by taking those needles out of working position to create floats. I'm really happy with the effect and feel a whole skirt in open banding would be really effective, or perhaps just as belting which is more subtle. My main direction at this point is a mash-up of wovens and knits which references early 20th century dressmaking techniques. In writing about process and also experimenting on my industrial knitting machines, I have been forced to engage in a sort of dual with them. I coax them into behaving and they reward me with beautiful original work. Bamboo and rayon bands in 2/48 and 2/60 nm. I am trying to make really narrow, really fine bands to run along seams and along the length of a persons body. Silk and merino yarns in 2/70nm on the left which are slightly terrifying (in terms of fineness) to work with. There is an old world quality to these bands because of the intersection of quality yarn and classic knit structure that I absolutely love. Lace veiling and silk banding with floats that imitate fagotting..... Here are some simple examples of silk fabrics on the bias coupled with belting ideas. If you squint can you envision a dresses? I can:)....

0 Comments

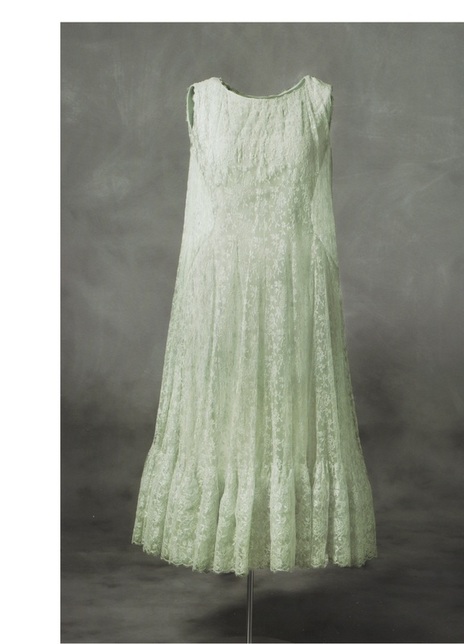

Stuart Hall states messages have complex structures of dominance. In his article “Encoding, Decoding” his central argument is fixed around the medium of tv. He breaks down the various ways in which the process of producing “is not a random moment”. This is different from semiotic meaning but the two can certainly be “read” or “received” as one in the same. Semiotic meaning tends to be encoded within layers of frameworks both technical and knowledge based. In the context of a tv show there is input, such as the content as deemed appropriate by those in charge and the way in which it is presented...which is influenced by semiotics and the framework of the tv show ...and then there is the output: the audience views the show through the tv, the tv distorts the filmed image and the audience digests the image on various levels.... The thing is I had never considered how a production process could drive or obfuscate the INTENDED meaning. So the process itself encodes or perhaps formats messages. In the context of fashion design or the sewing industry it is interesting to consider how the process of producing garments encodes and shapes meaning. Sewing industries may be broken down generally into industrial garment making, home sewing and art/ craft sewing. Each avenue shapes and provides a framework of technique and knowledge. This means that the idea and content supported via alternate frameworks may have different outcomes. Further where fashion is involved there may be multiple levels of industry. A slip from the 1920’s is made of components such as lace banding and manufactured cloth sewn together. The various processes which shape those components, the message intended by the designer and the production frameworks all influence the final result. If a designer has access to cloth that is only 60 inches wide, or can only find 3 inch lace banding where she needs something wider the levels of process, meaning and making are altered. Stuart Hall goes on to describe dominant ideas embedded in culture as “hegemonic”, they seem natural and perhaps invisible. The fashion process of construction and assembly is a great example where dominant ideas about sewing technology shape the medium of clothing as if the process itself were taken for granted. Few question and seek out alternate production processes. So what technical and knowledge frameworks are there? What alternate production processes exist? Well, many Modernist designers such as Vionnet and Schiaperelli eschewed dominant approaches and explored humor as content as well ideas about harmonious sewn structures. Balenciaga was another designer who applied knowledge frameworks borrowed from Japan to inform and shape his more western sewing process of producing. Desses, Armani, Gres, McCardell, etc. developed new content, developed alternate frameworks to develop fashion within technique and knowledge frameworks. Looking back we view and read the finished garments in the context of the fashion photo, the fashion runway or in the context of a museum exhibit, these final products of a cultural producers output through the production process obfuscate original meanings. Gres’ production process included haute couture aspects such as hand stitching and custom fitting. Her design process was also informed by the 3-d modelling of cloth onto actual bodies rather than on mannequins or by using technical drawings. Designs made by Gres’ may not have been possible through alternate forms of production.

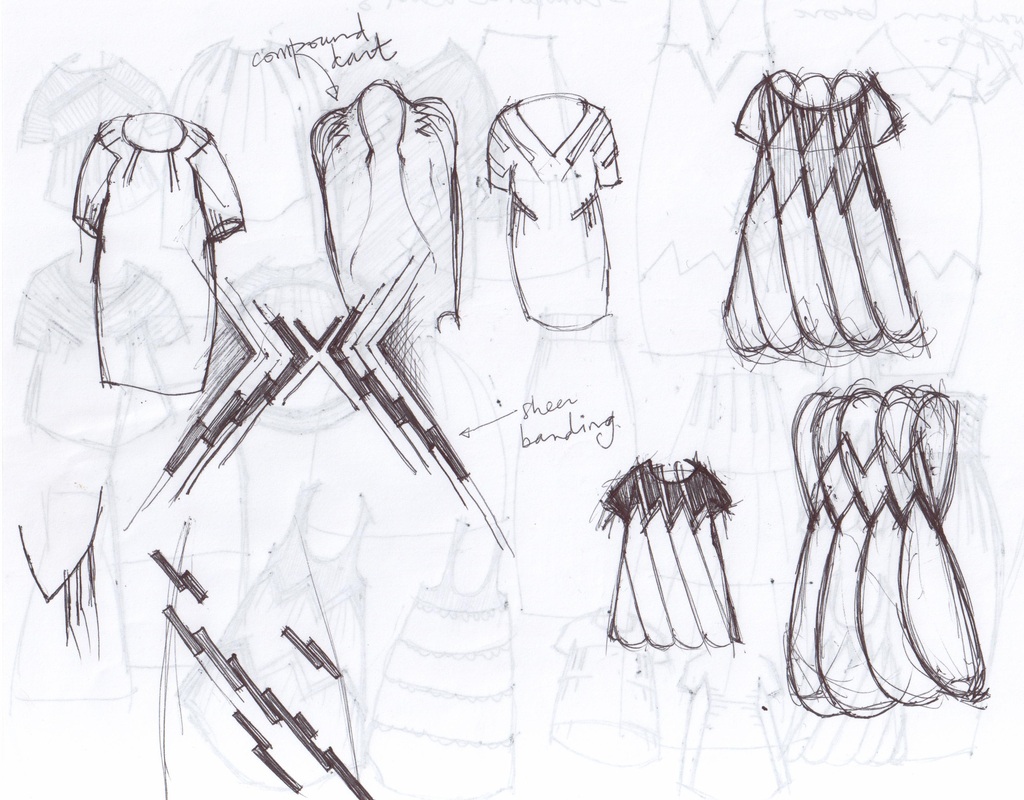

Current production processes which have the potential to alter outcomes might be laser cutting, digital fabric printing and knitting (as a way to control and form selvedge and edge structures). So you see production is really not a “random moment”, it formats, limits and influences the idea. Recently when I brought in some knit samples to our studio class, I was asked “why aren’t you knitting for your final project?” I have been thinking a lot about that as there is no real reason to adhere to woven or knit goods. Either one or both in combination may be relevant and there are many instances throughout fashion history where knitted fabric is used in a high fashion context. Both Gres and McCardell used knitted tubing. Custom knit lengths of silk and wool knitted goods were used in their work which at the time bore connotations of working class utilitarianism. I also think of Herve Leger and Rodriguez’s sexy almost architectural body conscious dresses. I wonder in what context is knitting relevant to my design research and how might knitted components be integrated with woven ones? My knitting machines (an industrial Dubied from the 1930’s and a Santagostino from the 1950’s) are capable of creating a multiplicity of forms based upon changing basic settings. As a generative direction, I intend on developing narrow firm banding, very wide firm banding and simple tube shapes with integral finished edges. These forms may be used in conjunction with woven fabric based forms to further develop my designs. This draws upon Vionnet’s pattern experimentation methodology which was rooted in a Classical simplicity that “saw the body as a spatial form.” This also draws more abstractly upon the use of highly decorative lace banding within Edwardian boudoir garments.

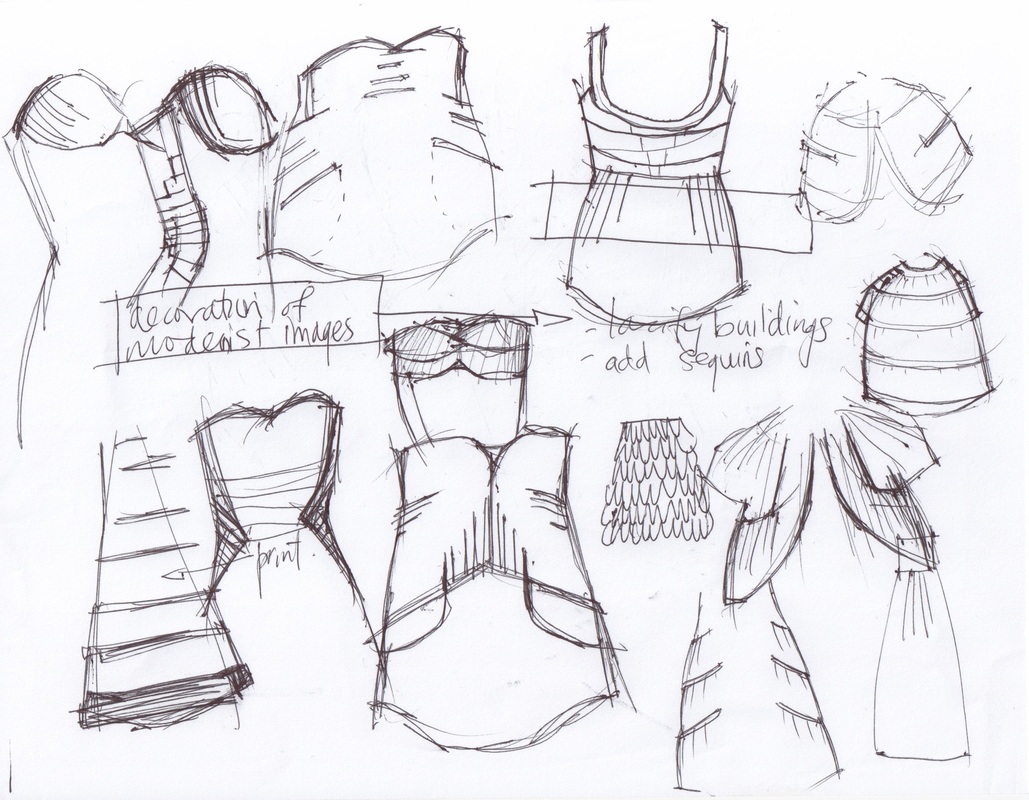

My research has dealt in large part upon the use of defunct pattern technologies as a path to innovation. Many aspects of couture are difficult to replicate and this need for competence keeps its techniques out of mass market. Perhaps also keeping it from being passed on... Techniques of knitting on the hand flat knitting machine may also be seen as marginalized by skill competence issues. Going forward I hope to locate silk, cotton and lurex yarns..... Developing a link between theory, practice and creativity in a master’s program is more difficult than I imagined. It seems easy enough to read, and critically reflect upon theory and somehow it feels just as easy to obsessively draw imagery based upon the sum total of information coming at me all the time. My process comes down to that of a sieve: one which is constantly weighing, filtering and separating components which feel prescient and special from the superfluous or boring.

My study focuses on how Edwardian social attitudes towards sex, female emancipation and leisure resulted in unique forms of boudoir clothing, which in turn heavily influenced Modernist clothing. As a result I am currently reading “A History of Modernism” by T.J. Clark. He conveys the slow burn which is the rise of Modernism and expresses its duality. Also close at hand is Loschek’s “When Clothes Become Fashion,” in it she discusses how recognizable clothing forms convey meaning and communicate ideas about identity and social structures. It is clear that clothing forms, as bizarre as they may be at times, are simply reflections of our complex social attitudes. Loschek discusses clothing as a “second skin”, but also as “a self referential system focused on self-organization” while Jennifer Craik asserts “clothing designs the body.” Going forward I aim to connect these broader scholarly concepts to Edwardian and Modernist attitudes more closely. Loschek explains “vestimentary fixation on the body is prescribed by a community’s communicative agreement on morality.” Edwardian boudoir clothing would have reflected a multiplicity of moral attitudes ranging from erotic and provocative to merely “an intimate sphere for the body. Sheer, yet loose garments were ornamental yet often basic in their geometry, connotative through the “power of their materials” such as expensive lace banding and detailed surface structures. As I work through my research I hope to correlate a connection between these Edwardian boudoir clothes to Modernist clothes through specific designers and garments, until then I leave you with some obsessive sketches.... |

Anna is a Hamilton based knitwear and textile practitioner blogging about her collection development as well as pre-1950's knitwear technology.

Links

Emma Gerard Make something bookhou Iben Hoej krystalspeck workshop bespoke truckee amy lawrence designs Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed